The History of Keluarga Pencak Silat Nusantara Indonesia

by

O'ong Maryono

In the beginning, KPS Nusantara was set up as an informal study group on July 28, 1968 in Jakarta by three young intellectuals: Mohamad Hadimulyo, Mohamad Djoko Waspodo, and Rachmadi Djoko Suwignjo. At that time they were disciples of two Setia Hati masters, Marijun Sudirohadiprodjo and Rachmad Suronagoro, and were active in the technical side of IPSI. The three also felt gravely concerned about the condition of pencak silat, because at that time pencak silat was losing ground to imported martial arts and sparked little interest among the educated youth. The growth of pencak silat was also constrained by the exclusive character of perguruan loath to open themselves up. In addition, IPSI -like many other institutions during the transition from the Old Order to the New Order- was suffering a financial and resource crisis that prevented it from playing an active role.

|

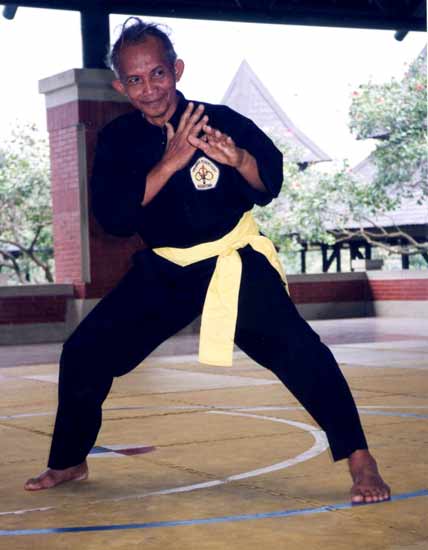

| Grandmaster Mohd. Hadimulyo is standing ready to fight. |

In an effort to help IPSI go through this difficult period and safeguard

pencak silat from vanishing from society, these three young pesilat

planned to set up a Study Group under their supervision to conduct

research into the different styles of pencak silat, and use this knowledge

to transform pencak silat from a traditional form of self-defence to a

modern sport. The realisation of this goal was not easy, since it went

against tradition. Because the SH pledge prohibited students from learning

at any other perguruan, they refused to undergo the keceran ceremony.

Still, after a hard struggle, they were able to convince their master,

Rachmad Suronagoro, to reveal to them 36 manoeuvres, keeping only the

core jurus secret. He also gave them his blessing to study at other perguruan

in the interests of the advancement of pencak silat. The 'unconventional'

attitude of the Study Group's founders did not upset their relationship

with SH, and until today members of KPS Nusantara are considered 'brothers'

by the members of SH, and vice-versa.

Mohamad Hadimulyo, Mohamad Djoko Waspodo and Rachmadi Djoko Suwignjo also

met with obstacles when they wanted to study in other perguruan as they

were suspected of wanting to steal secret techniques. This hurdle was

partly overcome thanks to the recommendation of Marijun Sudirohadiprojo.

He used his great authority in the pencak silat community to persuade

other masters to accept his former students. Over a period of several

years, the Study Group's founders travelled to different regions studying

different pencak silat styles. Among those they studied in depth were:

Cingkrik-Betawi pencak silat, under the master Mohamad Saleh; the West

Javanese styles of Cimande, Madi, Sahbandar, Kare and Taji, taught by

A'an, Marzuki and Hidayat, masters of the Matraman branch of PPSI; Pencak

Jawa Kombinasi under the guidance of Salamoen Projosoemitro; Pariaman

silat (Minangkabau) with master Itam; and Lintau silat under the guru

Amiruddin. Thereafter, they took the most effective and aesthetic movements

from these sources and combined them to form a new style, which aimed

to be national in nature, as reflected in the choice of its name 'Nusantara'

to refer to the Indonesian archipelago.

In the process of designing the Nusantara style, Mohamad Hadimulyo, Mohamad

Djoko Waspodo and Rachmadi Djoko Suwignjo held tightly to five principles.

First -like other rational-liberal schools- they considered pencak silat

as knowledge needed to be continually developed. For instance, Mohamad

Hadimulyo keeps on explaining to his students that:

Our perguruan was created with a desire to constantly seek out something, so that pencak silat evolves continually. Pencak silat is knowledge, and knowledge develops, it is never static. If human beings stop thinking, that is when stupidity begins.

Consequently, the founders of the Study Group worked to change old habits so that training could become more systematic. They felt that training material, curriculum, and the stages of learning must be clearly defined, and that tests and evaluations needed to be conducted regularly. Second, they decided to strictly divide the 'outer', physical aspect from the 'inner', spiritual aspect. Third, they believed that pencak silat olahraga could be competed, and were ready to pioneer a competition system to prove it. Fourth, they were open to learning from other forms of self-defence. Hadimulyo himself studied at the Jakarta Ju Jitsu Club under the leadership of M.A. Efendhi; while Mohamad Djoko Waspodo and Rachmadi Djoko Suwignjo learnt the Shotokan style of karate to the dan one level. Rachmadi Djoko Suwignjo even became a renowned practitioner of karate and won several prizes between 1970 and 1972. Fifth, and last, they agreed that in seeking effectiveness of movement, aesthetics could not be ignored. To succeed, pesilat had to execute attractive performances.

|

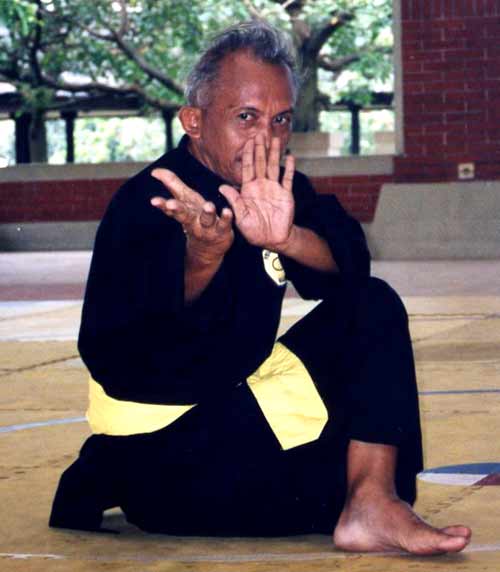

| Here Grandmaster Mohd. Hadimulyo is sitting down read to fight. |

Upholding these five principles, Mohamad Hadimulyo, Mohamad Djoko Waspodo

and Rachmadi Djoko Suwignjo, managed to create a new style of pencak silat,

which although originating from several styles, had a distinct identity.

Pencak silat observers rapidly got acquainted with its characteristics,

which one of the founders describes as follows:

In the Nusantara style, we are truly aware of the importance of expressing the softness of steps and stances, as well as the accuracy and effectiveness of offensive and defensive movements. Stances and steps are smooth and beautiful; form of stances very artistic; offensives simple and swift; and kicks firm, 'finished'.

In creating the Nusantara style, particular attention was given to improving pencak silat olahraga through trial competitions. As mentioned earlier, the Study Group and the Technical Committee of IPSI were able to blot out opposition from conservative masters who did not want pencak silat contested. With great zeal, the Study Group’s founders developed several match and competition systems, which would later be adopted by IPSI, thus influencing the design of the competition rules for pencak silat olahraga. Thanks to their services in 1973, the Nusantara Study Group was included among the top ten pencak silat organisations. If the majority of these top organisations were recognised for their role in setting up and developing IPSI in the 1950’s, Putra Betawi and the Nusantara Study Group were commended for their contribution to the development of pencak silat olahraga at the end of the 1960’s. Thanks to their support, IPSI succeeded in getting pencak silat accepted as a competitive sport in the National Sports Games.

Having won IPSI’s recognition, on July 28, 1973 the informal Study Group officially became a perguruan named Keluarga Pencak Silat (KPS) Nusantara. Unlike traditional schools, KPS Nusantara did not have an organisational structure centred on a master. In line with modern management, its rules and regulations separated the formal organisational structure from the personal relationship between master and students. Dependency on the charisma of the master was also limited by teaching standardised techniques through videocassettes, books, and other forms of communication media. Also, KPS Nusantara did not bind its students for life and –like other rational-liberal schools– chose to fulfil the ritual aspect with a perguruan pledge, opening and closing ceremonies at training sessions, and an opening salutation before performance. Also, to ensure the continuity of the school, a system of fees was applied in which the members and branches were required to contribute a certain amount to the parent organisation.

After becoming a perguruan, KPS Nusantara continued its efforts to standardise pencak silat olahraga and develop a suitable competition system. The perguruan also made a significant contribution to health education in general. Under the auspices of IPSI, between 1973 and 1975, Mohamad Hadimulyo, Mohamad Djoko Waspodo and Rachmadi Djoko Suwignjo, along with several sports experts from the Jakarta Sports Academy (STO), developed physical exercises that were adopted by the Department of Education and Culture to be practised in elementary, junior high and senior high schools on extra-curricular activity day, and were known as ‘Senam Pagi Indonesia’ (SPI or ‘Indonesian Morning Exercise’).

These technical reforms would not have been possible without effective training methods. By adapting the methodology of Western sports science –in particular the ‘synthesis-analytical’ or ‘part to whole to part’ method– the founders of KPS Nusantara designed a new method for training mastery in basic techniques, which was called ‘dasar-jurus-urai’ (‘basic movements-sequel movements-analysis of movements’). The study began with the most basic elements of movement, which were then configured into one complete movement. These complete movements were then combined into one sequence comprising several movements (jurus). Next, the jurus were broken down again to achieve perfection of form. The sequences became more complex by increasing the difficulty factor of the movements: from exercise manoeuvres, to competition manoeuvres, and ultimately, to defensive manoeuvres. In this way, graded training also functioned as a tool to spur progress, because students were constantly being confronted with new, and more challenging types of training. The following quotation explains this ‘dasar-jurus-urai’ method:

Training in straight punches begins with instruction about ways of clenching the fist, training in stationary punching, the ways of extending the arm accurately, and only then punching while stepping. This straight punch is then combined with various other movements to form one jurus. For instance it may be combined with an arm defensive and a combination punch to form an exercise manoeuvre. In training, this exercise manoeuvre is broken down again into training in basic punch movements, training in arm defensives and training in combination punches. And the use of each basic move is also analysed in detail.

Once the students have learnt the basic movements and jurus, they learn in depth their use through various types of training, starting with training in co-ordinating offensive-counteroffensive and offensive-counteroffensive-defensive techniques, before going on to restricted fight training, training in IPSI competition fights, free fighting without deckers, and finally armed contests using knives, machetes, short sticks, toya and chains. Students with special ability are given additional training in breathing, tensing the body, and punching hard objects and physical training in the form of general sports. These different kinds of training are given to students on the basis of their respective level of ability (Agoeng 1991:5-7), which is indicated by belts of different colours.

This systematic, clearly graded method of instruction facilitated en-masse training without neglecting the monitoring of mistakes and the evaluation of student progress. By focusing on the effectiveness of movement, the ‘dasar-jurus-urai’ training method could raise both self-defence and competitive skills in a relatively short time. Also, the intensive repetition of movements allowed students to attain optimal shapes. These advantages moved other rational-liberal schools to adopt the same training method, especially after the repeated successes of KPS Nusantara pesilat in national and international competitions, as shown by the tables at the end of this chapter. Although KPS Nusantara focused on the sports aspect, in contests of pencak silat seni or of technical ability –such as the Festival Pencak Silat Seni (Festival of Pencak Silat Art) held in Cirebon in 1982– this perguruan also won several prizes. What is more, KPS Nusantara became renowned for its daring to enter its pesilat into other self-defence championships, such as tae kwon do, judo and karate. For instance in 1976, a KPS Nusantara pesilat, Suhartono, won the first prize at the Kung Fu Asia Pacific Championships in Singapore. At the same championships, the KPS Nusantara team was elected as the best for its performance.

These successes did not always win the approval of the pencak silat community. Many masters reproached KPS Nusantara for being too focused on winning, and failing to address humanistic aspects in the study of pencak silat. The decision to separate sports techniques from philosophical and mystical elements, and the decision to do away with the rituals that bound the students together, were considered tantamount to eradicating the essence of pencak silat. In their eyes, KPS Nusantara was more like a sports club, where the pesilat do not profess their loyalty to the perguruan and get together only at the training location. Conservative and moderate masters also disagreed with the efforts of KPS Nusantara to reduce the influence of masters. They argued that the life of a perguruan has always revolved around the master, and that only a master is able to teach the skills and knowledge in an appropriate manner.

With regard to technique, KPS Nusantara was accused of abandoning the core pencak silat principles of jurus in its training, switching to modern sports methods. Combining pencak silat and other forms of self-defence was also unacceptable to traditional masters. They pointed out that the rhythm of breathing used by this perguruan was in fact taken from karate. Likewise, the locking techniques originated from ju-jitsu. Some even questioned whether the ‘combined’ style of KPS Nusantara could still be considered a style of pencak silat. Pencak silat supporters also criticised the ‘jagoan’ attitude of KPS Nusantara pesilat, and could not comprehend why they enjoyed taking part in other self-defence competitions. After all, according to tradition, a pesilat is not allowed to ‘experiment’ or demonstrate his ability outside the pencak silat community itself. What’s more their arrogant attitude was in no way befitting to pencak silat principle of nobleness of mind and character (budi perkerti luhur).

Initially, the founders and members of KPS Nusantara were indifferent to the criticisms thrown at them by other perguruan. They continued to chase their vision, expanding the reach of their perguruan by setting up branches in many regions in Java, Aceh, South Sulawesi, Central Sulawesi, South Kalimantan and Lampung. Satisfied with IPSI’s recognition of their role, and with their victories at national and international competitions, KPS Nusantara insisted that the path it trod was the right one, because pencak silat could develop only by employing a modern organisational structure and modern sports methods, and by freeing itself from tradition. If pencak silat failed to adapt to the demands of the age, it would continue to be misused as an instrument of conflict in society, or would disappear completely within a very short period of time.

|

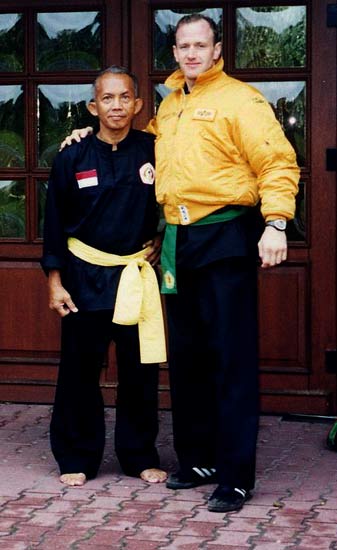

| Grandmaster Mohd. Hadimulyo poses with Andre Mewis in Berlin, 2002. |

But, beginning in the late 1970s, KPS Nusantara started to change its attitude and to acknowledge that some criticisms might contain elements of truth. For instance, the assumption that a perguruan could diminish the influence of masters by employing modern communication methods proved not to be quite the case. Up to now, the charisma of Mohamad Hadimulyo continues to inspirit KPS Nusantara, and there is no successor to replace him as yet; a situation that endangers the continuity of the school. The executive also had to admit that the organisational structure has not been particularly successful in fostering a ‘genuine’ sense of fellowship. Members no longer active in the perguruan eventually lost touch, because of the lack of routine communal events. Contact has even been limited with two of the three founders, Mohamad Djoko Waspodo and Rachmadi Djoko Suwignjo, after their withdrawal from the world of pencak silat at the end of the 1970’s. Another related issue was that seniors who have completed the physical training, could not enhance any further because KPS Nusantara did not concern itself with the spiritual aspect of pencak silat.

However, the main driving force behind KPS Nusantara’s re-thinking of its orientation was the gradual loss of prestige of pencak silat sports competitions. Its pesilat were less enthusiastic about competing in sports championships, and it proved difficult to recruit potential athletes. In the training, pencak silat olahraga began to wane, while the artistic and self-defence aspects gained prominence. This change was stimulated by KPS Nusantara’s disciplinary suspension from sports competitions in 1982, which forced the perguruan to mark its time giving displays of mass jurus performances at various sporting events. Only in the early 1990’s, did KPS Nusantara begin pioneering the standardisation of pencak silat seni and bela diri. In designing pesiladi and pesilani rules, Mohamad Hadimulyo once again provided valuable input to IPSI. Along with other pencak silat figures, he participated in efforts to re-integrate all aspects of pencak silat into the jurus wiraloka wajib. This obligatory category, encompassing aesthetics, physical ability and expertise in self-defence, was accepted by the founding members of PERSILAT in Jakarta on May 22-24, 1996, and was contested for the first time the following year at the 7th World Pencak Silat Championships in Malaysia.

Reflecting this shift in priority, KPS Nusantara has redefined its achievement target to include art and self-defence events. With singular enthusiasm, KPS Nusantara pesilat now strive to win pesilani and pesiladi competitions. Conversely, interest in participating in sports competitions has declined drastically and today only a few focus on this aspect, and even fewer manage to win gold medals. So, KPS Nusantara has de facto admitted that the modernisation of pencak silat cannot be based on developing the sport aspect alone. Like other rational-liberal schools, KPS Nusantara had to accept the fact that its prophecy did not come true.